President Bola Tinubu’s recent grant of state pardon to more than 170 individuals has stirred controversy, not merely for the names it contains, but for what has followed. The Attorney-General of the Federation (AGF) has announced that his office will be “reviewing” the list to ensure legal compliance. Yet, such a move, however well-intentioned, risks opening a floodgate of lawsuits and, more importantly, raises grave constitutional questions about the nature and limits of the power of prerogative of mercy under the 1999 Constitution.

Two questions lie at the heart of this matter. The first is whether the Attorney-General has the power to review a presidential pardon list once approved by the Council of State and published publicly or announced by the President. The second, and perhaps more fundamental, is at what point the act of presidential pardon under the Nigerian Constitution can be said to be complete and irreversible. These two issues are closely intertwined, for one cannot interrogate the Attorney-General’s power to review without first determining whether there remains anything left to “review” once the President has publicly published the list or announced the names.

The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria is clear. Section 175(1) vests in the President the power to “grant any person concerned with or convicted of any offence a pardon, either free or subject to lawful conditions.” But Section 175(2) immediately qualifies this by providing that the President “shall exercise the power after consultation with the Council of State.” That phrase is not cosmetic in nature. It was inserted to check the risk of abuse and to ensure that the exercise of mercy is guided by the collective wisdom of the nation’s highest advisory body. It subjects what might otherwise be a personal discretion into that which has a constitutional precondition. The consultation with the Council of State is a weighty constitutional precondition to valid and full constitutional exercise of the power of State pardon.

Under section 175(1) of the 1999 Constitution, the President may “grant any person concerned with or convicted of any offence created by an Act of the National Assembly a pardon, either free or subject to lawful conditions.” But this power, though vested in the President, is not one that he exercises in isolation. Subsection (2) provides that the President shall exercise these powers “after consultation with the Council of State.” This consultation is not cosmetic; it is a constitutional process intended to bring collective wisdom and public responsibility to an otherwise solitary prerogative. The president presents a list, the Council of State advises, but the President decides.

The critical balance here is that while the President is not bound to accept every recommendation made by the Council, he cannot act without consulting it. Consultation must precede and inform his discretion. Thus, once a list of recommended persons for pardon has been deliberated upon by the Council, the President may lawfully act only within the parameters of that consultation. He may, for reasons of policy or conscience, decide to exclude a name from the final list, but he cannot unilaterally add new names that were not part of the consultation. Any addition would require a fresh presentation to the Council for further consultation as mandated by section 175(2). In this sense, the President’s discretion operates within the bounds of prior advice, not beyond it.

It is against this backdrop that the Attorney-General of Federation’s recent statement must be examined. According to him, the “final administrative stage” of the clemency process involves reviewing the names and recommendations “to ensure full compliance with established legal and procedural requirements before any instrument of release is issued.” However, the Constitution does not confer on the Attorney-General any supervisory power over the exercise of the President’s prerogative of mercy at this stage. Once the President, acting after consultation with the Council of State, decides who to pardon and announces it, the Attorney-General cannot reopen that decision under the guise of “administrative review.” At that point its tad too late for administrative review, save for clerical errors and the likes.

A deeper constitutional issue is when does the act of pardon itself becomes complete. Is it when the Council of State gives its advice, when the President publicly publishes or announces the names, or only when a formal “instrument of pardon” is signed? Its good to note that the section 175 gives the condition for exercise of state pardon, but does not state that it must be gazetted. Section 175(1) speaks of the power to grant state pardon, and the Constitution does not condition the validity of a pardon on the signing or delivery of any particular instrument. The consultation is a procedural precondition; the public communication or official announcement of the President’s decision shows the substantive act of clemency in itself. The subsequent issuance of a written instrument is purely evidential and administrative.

The power of pardon under the Constitution passes through four legs: President (through a prerogative committee) comes up with a list. Consultation of the Council of State based on the list. The President’s formal decision and public announcement of the pardons; and the signing and issuance of instruments of pardon or release, which will then be transmitted to the Controller-General of Corrections or other relevant authorities. The critical question is whether the pardon becomes legally binding at stage 3, or stage 4.

The distinction between these two positions is not merely technical; it determines the very nature of the instrument of pardon. If the pardon comes into legal existence only when the instrument is signed, then the instrument is constitutive, it creates the right. If, however, the pardon is complete upon presidential announcement following Council approval, then the instrument is merely evidentiary or administrative, it documents and communicates what has already occurred substantively. This distinction is critical to understanding what powers, if any, the Attorney-General may exercise at the so-called “final administrative stage.

There are compelling arguments for the position that the signing of the instrument is an evidentiary or administrative act that formalizes what has already occurred substantively. Thus, once the President, having consulted and obtained the approval of the Council of State, publicly publishes or announces that certain persons have been granted pardon, the act of mercy is complete in law and effect. The instrument of pardon merely documents as evidence and communicates that decision to the appropriate authorities.

This interpretation finds support in fundamental principles of constitutional law, that where the Constitution vests a power in an office and prescribes the conditions for its exercise, the power is validly exercised once those conditions are met. Section 175 prescribes one essential condition: consultation with the Council of State. Once that consultation occurs and the President exercises his discretion to grant pardon, announcing his decision publicly, the constitutional act is complete. To suggest that the pardon remains conditional, uncertain, or revocable pending the signing of administrative instruments not mentioned in the Constitution would be to read into Section 175 requirements that the framers did not include.

Yet administrative practice supplies certain practical realities that cannot be ignored. The Constitution does not describe the detailed administrative form that must follow, administrative practice, however, supplies that form. After the President’s decision there follows a final administrative stage in which instruments are prepared, signed, issued and transmitted to the Controller-General of Corrections for execution or other necessary bodies. It is that administrative package, the signed instrument, communicated to the agency that controls liberty that produces the practical legal effect of release. The administrative act is also the substantive legal evidence that the beneficiaries of pardon can hold on to. Until the instrument is prepared and the relevant authority is properly authorized to act upon it, no operational change in an inmate’s status can lawfully occur.

This administrative necessity, however, does not transform what is essentially implementation procedure into an opportunity for substantive review. Even accepting that formal instruments must be prepared and signed before practical release can occur, constitutional practice demands that these instruments be executed within a reasonable time following the President’s decision. Indefinite “administrative review” would effectively nullify the President’s decision and the Council’s approval.

The question of whether an order of mandamus could compel the signing and execution of instruments for already-announced pardons is particularly relevant. Mandamus is a judicial remedy that compels the performance of a public duty, a corresponding legal duty in the respondent, and no adequate alternative remedy. If one accepts the position that the President’s public announcement following Council approval represents a completed constitutional decision to grant pardon, then the preparation, signing, and transmission of instruments becomes a mandatory ministerial duty, not a discretionary power subject to substantive review. At that point, the officials responsible, including the Attorney-General and ultimately the President himself, have no discretion to withhold or indefinitely delay implementation. Any beneficiary of an announced pardon could potentially approach the courts seeking mandamus to compel immediate execution of the instruments. The courts would then be called upon to determine whether the pardon is indeed complete upon announcement, making subsequent administrative steps mandatory, or whether the President retains full discretion until the moment of signing.

Such a mandamus application would place the burden squarely on the government to justify any delay or proposed modification to the announced list. If the AGF claims that administrative errors require changes, he would need to prove with concrete evidence, not mere assertions, that any discrepancies arose after the list was presented to, deliberated or approved by the Council of State. He would need to demonstrate that he is not conducting substantive reconsideration of the merits of individual pardons, but rather correcting purely administrative or clerical errors.

In the end, these legal questions, when does a pardon become complete, what authority does the AGF have over an approved and announced pardon list, can mandamus compel execution of announced pardons, and what constitutes impermissible delay, are constitutional in nature and ultimately for the courts alone to authoritatively answer. Different reasonable minds may interpret the same constitutional text in different ways. The position argued here, that the pardon is substantially complete upon presidential announcement following Council approval, making subsequent administrative steps ministerial rather than discretionary, is not the only possible interpretation. But it is a interpretation firmly grounded in the constitutional text, in the principle that constitutional acts are complete when constitutional requirements are satisfied, and in the practical reality that indefinite administrative review of completed constitutional decisions inverts the hierarchy of constitutional authority.

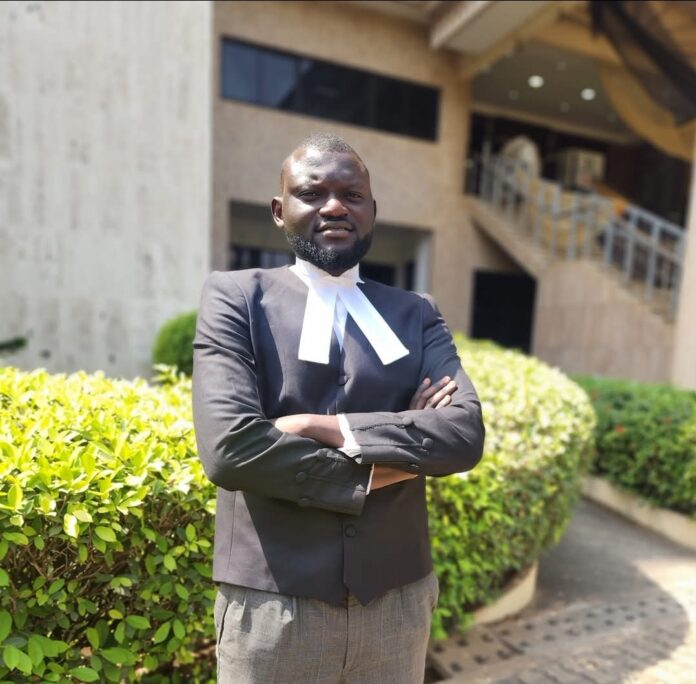

Opatola Victor is a Legal Practitioner with Legalify Attorneys and Solicitors and can be reached via victor@legalifyattorneys.com